Lecture 6

Resolution theorem proving

Summary of Transformation to Clauses

Resolution operates on sets of clauses, which is essentially a disjunctive normal form of formulas without existential quantifiers. Skolemization is the way to remove existential quantifiers at the cost of introducing new uninterpreted function symbols; skolemization preserves satisfiability.

From formulas to clauses

- negation normal form: propagate negation to atomic formulas

- prenex form: pull quantifiers to the top

- Skolemization: replace existential quantifiers with Skolem constants (not quantifier elimination!)

ALL x y. EX z. F

becomes

ALL x y. F[z:=s(x,y)]

where s(x,y) is a new function symbol of two arguments. You can think of Skolemization as a way of swapping quantifiers

EX s. ALL x y. F[z:=s(x,y)]

where s is existentially quantified. Because we are interested in satisfiability, we do not need to write EX s (and we cannot because we are in first-order logic).

- conjunctive normal form: each conjunct is called a clause

We typically do not write universal quantifiers either, because we know that all variables in a clause are universally quantified.

Term models

Resolution is

- sound (inference rules are correct)

- complete (inference rules are sufficient to prove all valid formulas)

This is remarkable because there are arbitrary models of first-order logic (sets, numbers, etc.) and yet if something is valid in all models there is a resolution proof of it. This follows from the fact that instead of considering all models, we can consider just term models.

L - all function symbols and constants in our language (including any Skolem functions). Assume at least one constant.

Term(L) - set of all ground terms in language L, give as the set T

T ::= c | f(T,...,T)

where c is a constant in L and f is a function symbol in L. So, Term(L) contains trees, syntactic structures. They are like algebraic data types in Ocaml. They are equal only if they are identical

if f(t1,t2) = f(s1,s2) then t1=s1 and t2=s2

This would not hold for any function f, but holds for terms because they do not evaluate things, just put things together, like pairs.

Resolution relies on the following property:

Herbrand's theorem: If a set of clauses in language L is true in some interpretation with domain D, then it is true in an interpretation with domain Term(L).

Proof sketch: If set  of clauses is true in interpretation

of clauses is true in interpretation  , then define interpretation

, then define interpretation  with domain Term(L) by evaluating functions as in the term model

with domain Term(L) by evaluating functions as in the term model ![Math $[[f]](t_1,t_2) = f(t_1,t_2)$](/w/lib/exe/fetch.php?media=wiki:latex:/img6be715e1bc090d262324b1f2a55cd3ed.png) , and defining the value of relations by

, and defining the value of relations by ![Math $[[R]]e_T = \{(t_1,t_2)\mid [[R(t_1,t_2)]]e = \mbox{true} \}$](/w/lib/exe/fetch.php?media=wiki:latex:/img0d306072b63994a1cd5215e09f22b10a.png) (end of sketch).

(end of sketch).

Note: this is in language without equality. With equality, we need to take equivalence classes of equal terms. So, in the presence of equality the term model can be finite.

Therefore, formula is satisfiable iff it has a term model.

Basic Idea of Resolution

Consider two clauses

¬F1 | R(x,f(g(y))) (1) ¬R(h(u),f(v)) | F2 (2)

that is

F1 -> R(x,f(g(y))) (1) R(h(u),f(v)) -> F2 (2)

Note that x,y,u,v are all universally quantified. Moreover, by Herbrand theorem we assume they all range over terms. We would like to see where R(x,f(y)) and R(h(u),v) overlap. To get as strong consequence as possible, we look for the solution of the equation on terms

x == h(u) f(g(y)) == f(v)

Unification

The second equation is equivalent to g(y)==v, so we get as a result the solution

x == h(u) v == g(y)

Such solution is called the most general unifier. We can represent it as substitution (x:=h(u),v:=g(y)). There are infinitely many unifiers, but all unifiers are instances of the most general one.

In general, unification is a way to solve equations in the term model. It's main uses are

- resolution theorem proving

- Prolog (particular resolution strategy)

- type inference for parameterized types (Hindley-Milner algorithm)

Unification algorithm: maintains a set of equations between terms.

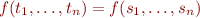

- deconstruct:

into

into

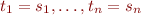

- if

is in the set for

is in the set for  and

and  distinct function symbols, report no solutions

distinct function symbols, report no solutions - reorient

into

into  for variable

for variable  and non-variable term

and non-variable term

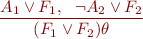

- if

is in the set and

is in the set and  does not occur in

does not occur in  , replace

, replace  with

with  everywhere

everywhere - remove

- if

is in the set and

is in the set and  occurs in

occurs in  (and

(and  is not

is not  ), report no solution

), report no solution

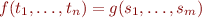

Resolution proof rules

Resolution

where  is the most general unifier of

is the most general unifier of  and

and  .

.

Factoring

where  is the most general unifier of

is the most general unifier of  and

and  .

.

Example

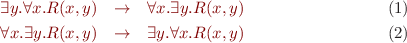

Trying to prove validity of

Proof that the formula(1) is valid, by proving that the negation of the formula does not end with a counter-example (same principle seen in lecture 5 to prove validity of loop invariant).

¬(∃y.∀x.R(x,y) ⇒ ∀x.∃y.R(x,y))

by: (A => B) <=> ¬A ∨ B

¬(¬∃y.∀x.R(x,y) ∨ ∀x.∃y.R(x,y))

by: ¬(A ∨ B) <=> ¬A ∧ ¬B

∃y.∀x.R(x,y) ∧ ¬∀x.∃y.R(x,y)

by: ¬(∃x.F) <=> ∀x.¬F and ¬(∀x.F) <=> ∃x.¬F

∃y.∀x.R(x,y) ∧ ∃x.∀y.¬R(x,y)

by: Skolemization

{R(x,s1), ¬R(s2,y)}

by: Unification R(s2, s1) where x = s2, s1 = y

emptyset

Proof that the formula(2) is not valid, by proving that the negation of the formula ends with a counter-example.

¬(∀x.∃y.R(x,y) ⇒ ∃y.∀x.R(x,y))

by: (A => B) <=> ¬A ∨ B

¬(¬∀x.∃y.R(x,y) ∨ ∃y.∀x.R(x,y))

by: ¬(A ∨ B) <=> ¬A ∧ ¬B

∀x.∃y.R(x,y) ∧ ¬∃y.∀x.R(x,y)

by: ¬(∃x.F) <=> ∀x.¬F and ¬(∀x.F) <=> ∃x.¬F

∀x.∃y.R(x,y) ∧ ∀y.∃x.¬R(x,y)

by: Skolemization

{R(x, s1(x)), ¬R(s2(y),y)}

by: Unification s1(x)=y and x=s2(y) then s1(s2(y))=y by: Adding a constant 'a'

R.{s1,s2,a} = L

Term(L) = {a, s1(a), s2(a), s1(s1(a)), …}

[R]eT = {(t,s1(t)) | t ∈ Term(L)} where eT: F ⇒ {true, false} and T ⇒ Term(L)

[s1(s2(a))]eT = s1(s2(a))

[∀.R(x,s1(x))]eT = true

∀t ∈ Term(L) [R(x,s1(x))]eT[x:=t]

∀t ∈ Term(L) ¬[R(s2(y),y) ] R(s2(y),y)]eT[y:=t]

[R]eT = {(a,s1(a)), (s1(a),s1(s1(a))), (s2(a), s2(s2(a))), …}

Then we should find a pair (tx,ty) s.t. (tx,ty) ∉ [R]. A possible counter-example is (tx,a) ∉ [R], ∀tx.

The fact that we have found a counter-example imply that the initial formula is invalid.

Consider case where R denotes less than relation on integers and Ev denotes that integer is even

(ALL x. EX y. R(x,y)) & (ALL x y z. R(x,y) --> R(x, plus(x,z))) & (Ev(x) | Ev(plus(x,1))) --> (ALL x. EX y. R(x,y) & E(y))

References

Theorem prover competition: http://www.cs.miami.edu/~tptp/

Hanbdook of Automated Reasoning: http://www.voronkov.com/manchester/handbook-ar/index.html

You can also check Chapter 8 of Gallier Logic Book.

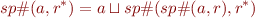

Abstract Interpretation

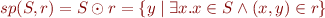

Strongest postcondition of loop

If we know the set S of reachable states at one program point, and we have command given by relation r, we compute

We have seen that a loop reduces to transitive closure of a relation, along with non-deterministic choice and assume statements:

while (F) c === (assume(F);c)*; assume(~F)

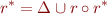

Recursive definition of transitive closure

We then have

If S was finite (and small), this would give us algorithm for computing the set of reachable states.

S is infinite, instead of S, we use a representation of some approximation of S. Because we want to be sure to account for all possibilities (and not miss errors), we use overapproximation of S.

Background on Lattices

Recall notions of preorder, partial order, equivalence relation.

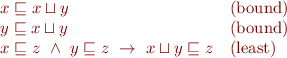

Partial order where each two element set has

- supremum (least upper bound, join,

)

) - infimum (greatest lower bound, meet,

)

)

So, we have

and dually for  .

.

See also Lattice (order) and, for more details, lecture notes by J.B. Nation or Chapter I of a Course in Universal Algebra.

Example Hasse diagrams for powerset of {1,2} and for constant propagation.

Properties of a lattice

- finite lattice

- finite ascending chain lattice

Basic notions of abstract interpretation

Let PS denote program states and  denote the set of all subsets of PS, so

denote the set of all subsets of PS, so  and

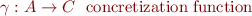

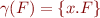

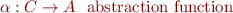

and  for a set of states S. We introduce an abstract analysis domain A and functions

for a set of states S. We introduce an abstract analysis domain A and functions

Instead of working with C, we work with simpler domain A, which is the data structure for analysis.

Examples of A:

- mapping from variables to information about the values they can have (interval analysis, sign analysis, constant propagation)

- formula F (usually in canonical form) such that

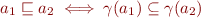

So, we will impose that our domain is partial order. It is useful to require additional property, namely that we have lattice, which have “union”-like and “intersection”-like operations.

Note that  allows us to define set-like operations on A that correspond to operations on A:

allows us to define set-like operations on A that correspond to operations on A:

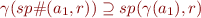

Instead of  , we have its approximation

, we have its approximation  . To be sound we need to have

. To be sound we need to have

This is the most important condition for abstract interpretation.

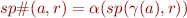

One way to find  it is to have

it is to have  that goes the other way

that goes the other way

such that

Then we can write a definition of  in terms of it:

in terms of it:

and we call this “the best transformer”.

Abstract computation of program semantics

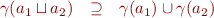

In our lattice we have

because of the way we defined order.

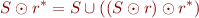

Then we rewrite our computation of sp for the loop by replacing  with

with  and replacing

and replacing  with

with  . We obtain fixpoint equation for computing the effect of a transitive closur eof a relation (i.e. a loop):

. We obtain fixpoint equation for computing the effect of a transitive closur eof a relation (i.e. a loop):

We can then iterate this equation until it stabilizes.

From the properties of  it follows that the result is approximation of the set of reachable states.

it follows that the result is approximation of the set of reachable states.

When does it stabilize? Note that the sequence is increasing and if we ever repeat we have stabilized. If there are no infinite ascending chains, the computation terminates.

Simple example with small ascending chains but large size: constant propagation.

Example analyses

- initialization analysis

- constant propagation

- sign analysis

References

- A wonderful tutorial by Prof. Cousot, explaining in fairly simple language what abstract interpretation is all about. Tutorial Abstract Interpretation