Relational Semantics of a Simple Language

We will next give meaning (semantics) for our Simple Programming Language using relations between initial and final state of each command. We illustrate the use of this semantics by showing certain very simple program equivalence properties.

When we write “x” we mean the variable named x viewed as a syntactic object (string or a node in syntax tree). We sometimes omit quotes.

Examples of Semantics for Some Programs

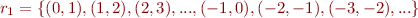

In such a semantics, if the state of the program is given by one integer variable x, then the meaning of this 'increment program':

x = x + 3; x = x - 2

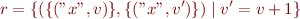

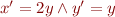

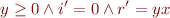

is the relation  .

.

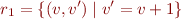

A pair of integers  is in relation, written

is in relation, written  , if and only if

, if and only if  . Using set comprehensions, we write

. Using set comprehensions, we write

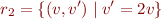

The meaning  of

of

x = x + x

is

The meaning of

while (true) { }

is empty relation.

Why Relations

The meaning is, in general, an arbitrary relation. Therefore:

- For certain states there will be no results. In particular, if a computation starting at a state

does not terminate, then for no

does not terminate, then for no  will there be a state of the form

will there be a state of the form  in the relation.

in the relation. - For certain states there will be multiple results, when

and

and  for

for  . Intuitively, this means command execution starting in

. Intuitively, this means command execution starting in  will sometimes compute

will sometimes compute  and sometimes

and sometimes  . Verification of such program must account for both possibilities.

. Verification of such program must account for both possibilities. - Multiple results are important for modelling e.g. concurrency, as well as approximating behavior that we do not know (e.g. what the operating system or environment will do, or what the result of complex computation is)

Program States, Relations on States

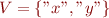

Our programs can have any finite number of integer variables. Let  denote the set of variable names such as 'x' in the example above. The state of our program is a function

denote the set of variable names such as 'x' in the example above. The state of our program is a function  mapping variable names to their values, and the set of states

mapping variable names to their values, and the set of states

is the set of all such functions. We assume that the range of variables is  (the set of integers), but most of what we say will be independent on whether the variables are integers or have some other type.

(the set of integers), but most of what we say will be independent on whether the variables are integers or have some other type.

In the above increment program,  and a state is of the form

and a state is of the form  for some integer

for some integer  (recall that we represent each function

(recall that we represent each function  as relation

as relation  ). So the increment function is given by a relation, call it

). So the increment function is given by a relation, call it  , that takes the state

, that takes the state  and maps it to state

and maps it to state  :

:

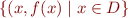

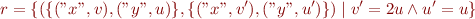

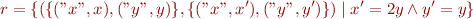

What happens when we have more than one variable? Let  and consider this program:

and consider this program:

x = y + y

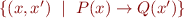

The meaning of this program is given by relation

Renaming variables so the initial value of variable “x” is denoted  and final value denoted

and final value denoted  , we have

, we have

I will call the relation r the relational semantics of this command and the formula  the formula semantics of this command.

the formula semantics of this command.

When we have multiple variables, we can give semantics to assignment statements using function update notation. Regardless of the number of variables in  , the relational semantics of x=y+y; is

, the relational semantics of x=y+y; is

![Equation \begin{equation*}

r = \{(s,s["x" \mapsto 2 s("y")]) \mid s \in S \}

\end{equation*}](/w/lib/exe/fetch.php?media=wiki:latex:/img53a76738003779b1ca6076a2b6dedf76.png)

Semantic Functions

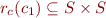

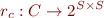

Let  denote the set of all commands (programs). Our goal is to define semantic function for commands, denoted

denote the set of all commands (programs). Our goal is to define semantic function for commands, denoted  (relation of the command), which maps each command

(relation of the command), which maps each command  into its relational semantics

into its relational semantics  . Formally,

. Formally,

To define meaning of statements such as x=y+y; we need a way to evaluate a term such as y+y in a given state. We introduce function  (function of the term), which maps a term into a function from states to values:

(function of the term), which maps a term into a function from states to values:

Meaning of Assignment

Given some definition of  , the meaning of the assignment statement is simply

, the meaning of the assignment statement is simply

![Equation \begin{equation*}

r_c(x=e) = \{ (s,s["x" \mapsto f_T(e)(s)]) \mid s \in S \}

\end{equation*}](/w/lib/exe/fetch.php?media=wiki:latex:/img9cee5d8e9d631c09341d405adba1e2e1.png)

Meaning of Terms

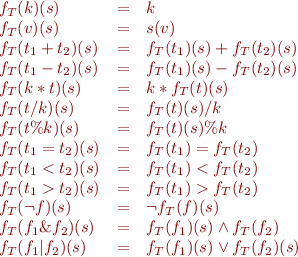

We next define meaning of terms, whose syntax we defined earlier.

T ::= K | V | (T + T) | (T - T) | (K * T) | (T / K) | (T % K) F ::= (T=T) | (T < T) | (T > T) | (~F) | (F & F) | (F|F) V ::= x | y | z | ... K ::= 0 | 1 | 2 | ...

The recursive definition corresponds to a program you would write in e.g. Scala to compute the value of an expression in a given state when writing an interpreter.

Based on that context-free grammar, we can define recursively the terms semantic :

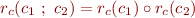

Sequential Composition as Relation Composition

To execute a statement sequence, we execute the first statement and from the resulting state execute the second statement. We therefore define statement sequential composition as relation composition of statement meanings:

Example: commuting assignments

Consider the task of a programmer or a compiler who wishes to reorder two assignment statements, converting

x = e1; y = e2

into

y = e2; x = e1

where  and

and  . Under what conditions will these two program fragments have the same meaning?

. Under what conditions will these two program fragments have the same meaning?

To answer that question, we just have to derive these two expressions :

![Equation \begin{equation*}

\begin{array}{lll}

& & r_c ( x = e_1 ; y = e_2 ) \\

& = & r_c ( x = e_1 ) \circ r_c ( x = e_2 ) \\

& = & \{ ( s , s[ "x" \mapsto f_T(e_1)(s) ]) | s \in S \} \circ \{ ( s , s[ "y" \mapsto f_T(e_2)(s) ])~|~s \in S \} \\

& = & \{ ( s , ( s["x" \mapsto f_T(e_1)(s)] )["y" \mapsto f_T(e_2)( s["x" \mapsto f_T(e_1)(s) ] ) ] ) )~|~s \in S \}

\end{array}

\end{equation*}](/w/lib/exe/fetch.php?media=wiki:latex:/img2b96511a8ee5da30cef5d1198eb0e093.png)

Symetrically, we have:

![Equation \begin{equation*}

\begin{array}{lll}

& & r_c ( y = e_2 ; x = e_1 ) \\

& = & \{ ( s , ( s["y" \mapsto f_T(e_2)(s)] )["x" \mapsto f_T(e_1)( s["y" \mapsto f_T(e_2)(s) ] ) ] ) )~|~s \in S \}

\end{array}

\end{equation*}](/w/lib/exe/fetch.php?media=wiki:latex:/imgc73a4594ea0b2e9fbea5db0002c06fec.png)

Thus, if y is free in  and x is free in

and x is free in  , these two fragments will have the same meaning.

, these two fragments will have the same meaning.

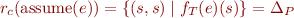

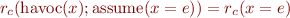

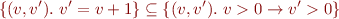

Assume Statement

Assume statement is a useful declarative statement, which we will use to define the meaning of several remaining commands. The meaning of assume is simply is the diagonal relation, which produces no resulting states if the given expression is false, and does nothing if the expression is true:

where  .

.

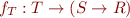

Non-deterministic Choice as Union

Non-deterministic choice is another useful declarative statement, which non-deterministically chooses to execute one of the two statements. We use it to express other statements, as well as to model branching with conditions that we cannot express in the language. Its meaning is simply union of relations:

![Equation \begin{equation*}

r_c(c_1\ \mbox{[]}\ c_2) = r_c(c_1) \cup r_c(c_2)

\end{equation*}](/w/lib/exe/fetch.php?media=wiki:latex:/img329f48bf1f1138be81e76123251fc2dd.png)

Representing if-then-else Using Non-Deterministic Choice and Assume

We will define the semantics of

if (F) then c1 else c2

as the semantics of

(assume(F); c1) [] (assume(~F); c2)

Note that we are using non-deterministic choice, but exactly one of the two statements in the non-determinitic choice will succeed.

Exercise: expanding the definition of conditionals

We can also express this semantics directly as:

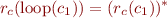

Non-deterministic Loop as Transitive Closure

Just as we use non-deterministic choice (union) to represent conditional statment, we use non-deterministic loop statement (transitive closure) to represent while loops. A statement loop( c ) executes statement c any number of times, possibly zero. Its meaning is transitive closure of the meaning of c.

Expressing While using Non-deterministic Loop

We define semantics of

while(F) c

as the semantics of

loop (assume(F);c); assume(~F)

Why does this definition make sense? It will be union of relations of the form:

(assume(F); c)^n assume(~F)

for all n. But if the value of n is wrong the result will be empty relation:

- if it executes even if F is false, then assume(F) will give empty relation

- if it stops even if F is true, then assume(~F) at the end will give empty relation

Therefore, the result is equal to the correct number of execution times.

Summary of Simplifying the Language

Instead of

c ::= x=T | (if (F) c else c) | c ; c | (while (F) c)

we can have language

c ::= x=T | assume(F) | c [] c | c ; c | loop c

Applying it to a multiplication example, we obtain

r = 0; i = y; loop ( assume (i > 0); r = r + x; i = i - 1 ); assume (i <= 0);

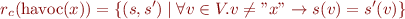

Havoc Statement

Havoc statement is another useful declarative statement. It changes a given variable entirely arbitrarily: there will be one possible state for each possible value of integer variable.

Expressing Assignment with Havoc+Assume

We can prove that the following equality holds under certain conditions:

In other words, assigning a variable is the same as changing it arbitrarily and then assuming that it has the right value. Under what condition does this equality hold?

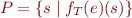

Summary of Correspondence between Programs and Relations

| program construct | relational meaning |

|---|---|

| sequential composition | relation composition |

| branching | union |

| loops | transitive closure |

| assignment | update of one state component |

| havoc | arbitrary change of one state component |

Control-Flow Graphs, While Theorem: One Loop is Enough

- from programs to control-flow graphs: transformation rules

- interpreter running over control flow graph

- normal form using only one loop and one extra variable

Sum of all matrix elements as control-flow graph and as one loop.

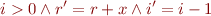

Proving Program Properties

A general approach:

- compute semantics of a program as a mathematical object (e.g. relation)

- prove that the relation satisfies the desired property

Example

Consider the code

r = 0; i = y; while (i > 0) ( r = r + x; i = i - 1 )

We represent it as

r = 0; i = y; loop ( assume (i > 0); r = r + x; i = i - 1 ); assume (i <= 0);

We compute the meaning of

assume (i > 0); r = r + x; i = i - 1

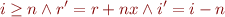

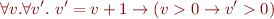

as the relation  whose formula is

whose formula is

We then wish to compute the transitive closure  .

.

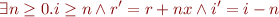

We claim that for every  relation

relation  is given by formula

is given by formula

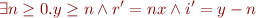

We can prove this claim by induction. The union of these relations is then given by

From there we can derive the meaning of

r = 0; i = y; loop ( assume (i > 0); r = r + x; i = i - 1 )

as

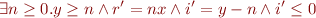

which when composed with assume( ) = assume(

) = assume( ) gives

) gives

which is equivalent to

This is the semantics of the above code.

Relations as Specifications

Nondeterministic programs can be used to specify other programs

If  is relation representing program and

is relation representing program and  relation representing specification, we say that program meets specification iff

relation representing specification, we say that program meets specification iff

Example:

This allows us to prove that programs satisfy their contracts, expressed using preconditions and postconditions:

void f()

requires x > 0

ensures x > 0

{

x = x + 1;

}

What is the relation for contract with

- precondition

- postcondition

Answer:

The correctness condition:

reduces to:

Further reading

- C A R Hoare and He Jifeng. Unifying Theories of Programming. Prentice Hall, 1998

- Semantics-based Program Analysis via Symbolic Composition of Transfer Relations, PhD dissertation by Christopher Colby, 1996